I’ve been holding off on writing this post for a while. It seemed impossible to do without including an element of personal experience, and when I started this blog I was very clear that it wasn’t about me. On the other hand, I was also sure that I didn’t want it to be anonymous: I want to be able to point to real experiences, where appropriate.

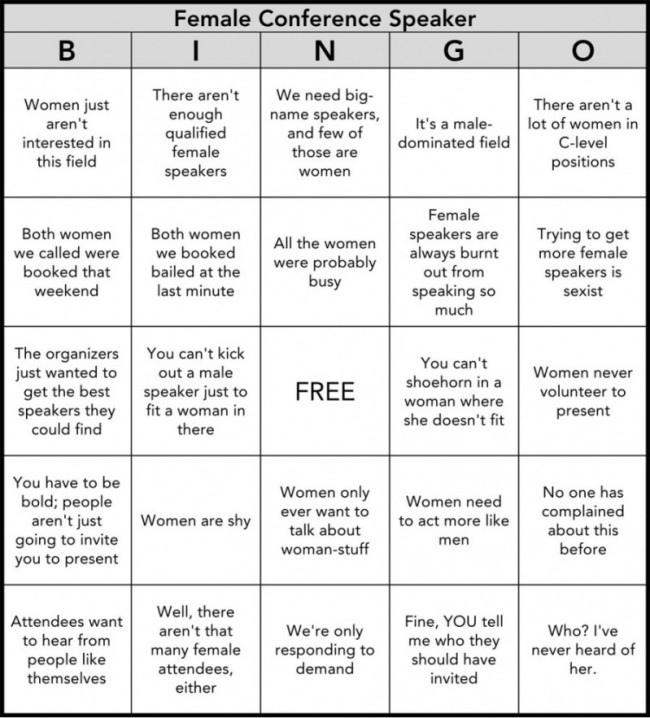

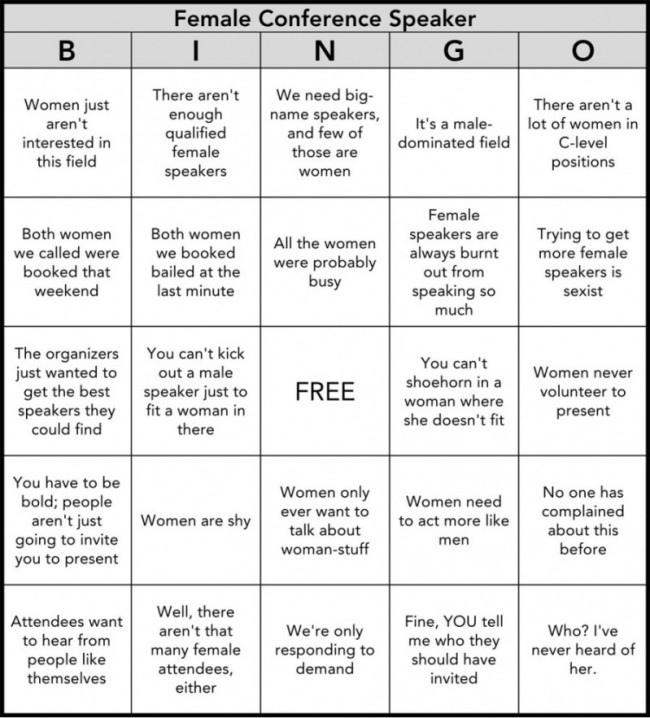

I will start by celebrating two things: that the way I discovered the current ICQC sausagefest was via a male colleague who is both opinionated and able to call these things out on twitter. Secondly, that the next thing I saw was a petition on change.org, laying out the issues clearly, and set up and signed by three women who are prominent quantum chemists. One of them is even one of the four women who are current members of the academy,* who run these conferences. There are a few other causes for celebration, including write ups in Nature, Salon, the discovery of the women in theoretical chemistry web directory, and sensible things written by other scientists, such as here, and here. There is also the bingo card, which I’ll copy here from feministe.

So that’s the positive response, summarised: is there much I have to add to this?

Well – yes. As someone who has been to three of the last four conferences in this series, in 2003, 2009, and 2012, as well as to one or two sausagefests, I think I have one or two things to say. These are good conferences. The standard of talks is very high: this is, however, guaranteed at the cost of making the talks invitation only. This makes them a little tricky to get to, at a particular point in your career: it tends to be easy to justify travelling to a conference to present a poster as a student or postdoc, a lot harder later in your career once you get used to speaking at conferences. I’ve always considered it worth it, because I learn a lot: an additional benefit is that because all the talks are invited, the talks are all held in one room – this results in a sense of community that you don’t get at other conferences of a similar size, which typically fit more speakers in by running parallel sessions.

This format, however, has the drawback that the nature of the conference is very heavily determined by the list of speakers chosen by the organising committee. For ICQC2015, before the petition got them to take it down, the list comprised 24 men, with perhaps a dozen more names still to come. The organisers protested that they had invited one woman, when they sent out their 27 invitations: unfortunately, she had not responded. The real issue is that they seemed to think that this was ok.

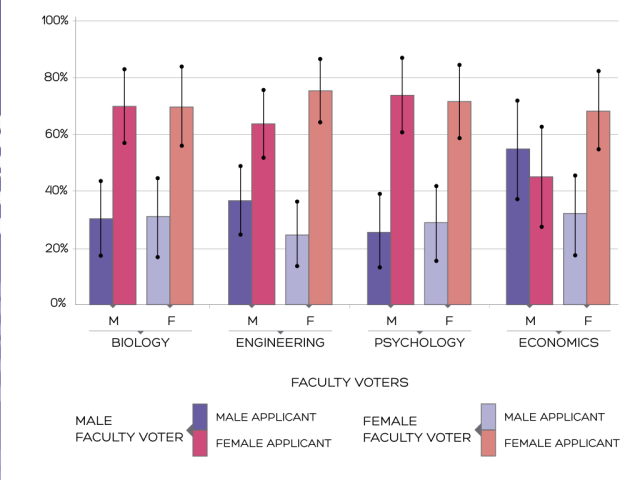

I won’t write any more about the generic problem, because it has been covered pretty well already. I’ll also mention the coverage on Inside Higher Ed, and on ChemistryWorld. But what I want to do here, is think about what it really going on in Quantum Chemistry. Is it ok, because the number of invited speakers represents the membership of the academy? Or should the list of speakers (and, dare I say, the membership of the academy) be reflective of the proportion of women working in the field?

I am writing this from one of the most carnivorous sausagefests that I have ever had the pleasure of being invited to. In fact, I am aware that I am here because the conference was called out on twitter for being a sausagefest, and I was subsequently invited publicly, again via twitter. I can indeed confirm, that being invited to speak at a conference to make up the numbers feels … different. There is however, an important difference here. I am not just the only woman to have spoken so far (thankfully, there is another one! coming up later this morning), but for extended periods of the conference, I have been the only woman in the room. However, there is very little point in feeling self conscious about being the only woman in the room, when you are well out of your depth already in speaking at a computer science conference – here, I have much bigger things to worry about. And it turns out that that’s ok: I’m pretty comfortable speaking to computer scientists about my science, and how parallel computing can be used to do really cool things – as it turns out, they are really quite happy to listen.

On reflection, I realise – with some startlement – how very, very comfortable I am, being the odd one out. I have thick skin. I have well developed coping strategies. I am very comfortable, in an environment such as this. But when I think about what that means … it makes me very, very, sad.

To state the bloody obvious: it should not be necessary to revise all of your expectations of social interaction in order to fit into your (YOUR!) professional environment. And I’m not saying, by the way, that I’m particularly socially awkward. But I spent a year as an exchange student in Japan when I was 15 – this was before both email and affordable international phone calls – and it was a pivotal experience in my adolescence. I am really, really comfortable, not fitting in. This should not be a prerequisite for a career in science.

At the 2012 ICQC, I had an interesting experience at the conference dinner. An epiphany or sorts, which I am actually quite grateful for. I’ve avoided writing about it until now, because I think the conversation about sexism in science can be had without reference to personal experience. But this post has already had far too much to say about me, so: here goes.

I’m at dinner, seated with a group of five, four of whom I know quite well. At some point, a member of the Academy comes over to speak to the person sitting opposite me. It’s a question about one of the talks that morning: an old idea, once dismissed, that is being revised for a new application. The conversation covers a little of the history of the idea, a couple of specific papers; the two of them talk for a couple of minutes, with no one else at the table having anything to add.

The visitor turns to me. “I’m sorry, we must be boring you”. I smile, assure him that this is not the case. “Oh, but you aren’t one of us, are you?” (I actually hadn’t clicked at this point – I had absolutely no idea where this was going.) So he continued. “What I mean is, you aren’t a scientist, are you?” At this point, conversation at the table has stopped: everyone is listening. I manage to come out with:

“Actually, yes I am”.

His forehead wrinkles, he smiles.

“Oh – what kind of science?”

“What I mean is, you aren’t our kind of scientist, are you?”

The silence grew. I fumbled for my conference name tag, which was hanging around my neck, and said something – I don’t know what, but I remember wishing for an equally brief english equivalent of the french si, and then I headed for the bar.

It was a weird conversation, and odder yet in that it happened right in front of a number of people who I have known for a long time. All men, of course. And this is where the epiphany comes in.

There were a large number of tables at this dinner; it is not a small conference. There is also a hierarchy in the way that people sit: at the tables behind me, there was a 50:50 gender split: those were the tables where the students and postdocs were sitting. In the central band of tables, where I was, many of the tables were full of men, though a few had a single woman (exhibit A: me). At the tables in front of us, seats had been reserved for VIPs: members of the academy, medal winners. At those tables, there was again a 50:50 gender ratio; this was because those men had brought their wives.

I’ve told this story to a few people, and the reactions differ quite significantly. But the age of the man who visited our table is a factor (he’s in his eighties**). The response goes, especially from those who know him, that

“He’s old. You can’t expect him to understand that the world has changed. It will get better”

Well, I like the optimism. But unfortunately, I do not think it is justified.

This is an educated, intelligent man. He has lived, and experienced, much more of the world than I have. He lived through the 60s, and the 70s, for goodness sake! How can he not be aware that the world has changed – by all rights, he should know a lot more of the history of feminism than what I do. I get trolled, often enough, by male students in their twenties who think that being a white male is to be discriminated against: well, I’m ok with the fact that they have something to learn. But the idea that, by virtue of their advanced age, we should excuse people from having to think about these matters? That I do not accept.

If we wish to give people a free pass on their responsibility to understand the modern world, then fine. But then do not tell me that these people are the authorities, no the arbiters, of scientific excellence. This is the feedback loop that is perpetuating outdated social mores in OUR community; this is why science is sexist.

*there have been 5 women over the history of the academy, 153 members in total: 3%

**I say this in the knowledge that it will not help to identify the member of the Academy in any way: men in their eighties are a significant demographic